In Conversation: Finding Solutions to End Plastic Waste

With Stew Harris (American Chemistry Council) and Marcus Eriksen (5 Gyres Institute), facilitated by John Ehrmann, Meghan Massaua, Pooja Tilvawala, and Debbie Welles of Meridian Institute

How do we reduce substantial plastic leakage into the environment—one of the greatest challenges we face as a society? In Summer 2020, Meridian brought together Marcus Eriksen of the 5 Gyres Institute (an environmental NGO) and Stew Harris of the American Chemistry Council (a plastics industry trade organization) for a conversation on how to achieve this shared vision. They represent historically-opposed communities on the issue of plastics, but our conversation illuminated many shared values and ideas—as well as some differences of perspective that leave us excited for further dialogue.

In the interview below, Marcus and Stew discuss approaches for inspiring innovative solutions and redesigning systems to increase circularity and reduce residuals and waste. They also explore the role of science, extended producer responsibility, systems thinking, reuse models, the role of plastic bans, and more.

Note: The conversation has been excerpted and edited for clarity. Marcus and Stew’s viewpoints by no means represent those of all NGOs or of all industry, respectively. They agreed to participate in this candid conversation to serve as an example of the benefits of conversation between two leaders in their fields who would not normally be expected to share their views in this manner. Although the decision to engage in such a collaborative discussion is not without risk, both are committed to fostering a clearer understanding between groups whose perspectives may differ. Meridian is grateful for their time and dedication.

Informing decision-making with science

MERIDIAN: In discussing how to tackle this complex problem, one place to start is by exploring the role of science. How can science help us move from division to action?

STEW: Achieving an appropriate balance between modes of data collection to inform decisions, especially between peer-reviewed science and citizen science, is an important issue for industry. To save time, we must use the best available science to make decisions now and then strive to improve that.

MARCUS: That’s true. We have enough information to act, but that doesn’t mean we should stop seeking greater understanding. One clear research need I see is quantifying the amount and types of material leaking into the environment. Improvements in our understanding of where leakage is occurring will help determine the success rates of projects and initiatives, as well as where to target future interventions. Still, this is not a reason for inaction. We must move forward now with initiatives to reduce plastic waste generation and correct our course as more information becomes available.

One of the values of citizen science is that it can act as an early alert system to highlight areas requiring more attention and further investigation through traditional approaches. (Stew)

STEW: I agree, and one way to supplement our understanding is through citizen science, which if performed through reliable and responsible methods can help tackle the need to gather data from the large geographic areas we are trying to understand. While citizen science is not a replacement for the more traditional peer review model, one of the values of citizen science is that it can act as an early alert system to highlight areas requiring more attention and further investigation through traditional approaches. Citizens can identify problems, questions, and challenges in their communities and in the environment, to call attention to the need for more rigorous academic review.

MARCUS: Yes, citizen science is like a canary in the coal mine, and scientists can follow the call. Citizen science cannot replace peer-reviewed science, but it can help give us an early warning and drive the conversation upstream. Moreover, science is building a foundation for a preventative strategy recommending the most cost-efficient way to solve the plastic waste problem—at its source.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) as a funding mechanism

MERIDIAN: How can we fund interventions to stem the tide of plastic leakage? Is Extended Producer Responsibility (or EPR, a system in which manufacturers bear a significant degree of responsibility for the environmental impacts of their products throughout the product lifecycle) a viable solution? Should industry bear more responsibility here?

STEW: This is an evolving conversation. An EPR program/policy that is material neutral (i.e., doesn’t only consider plastics) could be a viable solution for addressing a broader variety of products and improving the capture of these materials within a recycling system. Several stakeholders have expressed concern about the lack of clarity on how funds from EPR programs (such as bottle bills) are collected and used. It is important to first understand the solutions that need to be funded as well as the options for funding them. We know there are successful examples of EPR programs, but they are not without their challenges, especially when funds get diverted for other purposes.

MARCUS: I agree with material neutrality. However, I don’t look at the EPR issue through the material lens. Rather, I focus on the harm we’re trying to mitigate and the materials which are causing the most social, economic, and environmental harm—and are therefore the costliest materials. It’s great to hear that industry is thinking of what EPR models might work best, rather than rejecting them altogether. There are proposals with potential solutions. The Consumer Brands Association, for instance, is exploring a fee on virgin resin. Australian philanthropist Andrew Forrest, founder of Minderoo Foundation, has offered a similar ambitious proposal. This could be a way to fund recovery from the “Last Mile,” which focuses on the difficulty and logistics of delivering goods to the end user/final destination as efficiently as possible. Business is good at getting products to the most remote places on the planet, but the return voyage is left to cities and taxpayers. This is the essence of the challenge with the linear economy.

Many NGO leaders believe that an upstream fee on the pellets is the missing solution to incentivize the circularity of materials to make sure plastic waste can be responsibly managed. A fund provided by industry could make this possible, especially at a time when taxpayers and municipalities are overburdened and simply can’t afford to manage plastic waste any longer.

STEW: ACC is evaluating the Consumer Brands Association proposal, especially fees for all types of packaging. Details of how that funding is allocated and who will pay still need to be identified. However, we recognize there’s a role for producers in helping to fund these systems. At a high level, the proposal recognizes that there is a role for the various stakeholders in the value chain (e.g., producers, government, consumers) to play in order to sufficiently fund a system that captures materials and moves toward a circular economy. Without these components working together, we’re left with the systems that we have today—insufficient, underfunded, and stressed. We haven’t figured out the best system yet, but we’re clearly moving in that direction.

Systems thinking: a holistic approach

MERIDIAN: Speaking of systems, this conversation highlights a variety of intervention points in the value chain that could lead to solutions—from production of resins, to fashioning those into a product, to consumer use, and finally to post-consumer value. How can holistic approaches help us understand connections between parts of the system, and what we need to change to reduce detrimental impacts?

MARCUS: For NGOs, the high-level goal is zero plastic waste leakage into our environment. It seems industry concurs; they acknowledge that consumers and others do not want these materials to cause harm in the environment. NGO leaders often present three sets of systems-level solutions to avoid creating a legacy of waste:

-

- replacing petroleum-based plastics with alternative biomaterials that can readily biodegrade,

- creating zero-waste cities, and

- establishing novel ways to move goods through a reuse economy.

While these are the three big system changes we are working towards, there are also many private sector companies, especially young, innovative companies, that are on board and embracing the idea. They’re actively positioning themselves because they know doing so will capture the full lifecycle of their materials, which has value to customers. Furthermore, for big systems change, we need to address durable goods (defined as consumer goods that do not wear out quickly and typically are designed to last three-to-five years) and single use plastics differently, since their costs, benefits, and waste management methods differ.

STEW: These solutions all have a role in creating a zero-waste future. We share the common goal of eliminating plastic waste from the environment, but sometimes we take that for granted. Achieving this goal will require system-wide solutions. Industry’s perspective on systems thinking is innovation; not just in developing new materials, but also in novel ways to build infrastructure, move goods, assess logistics, and deliver products in different contexts. A next step is to work with other stakeholders to determine if there are ways to better package and deliver products to reduce waste and to increase recyclability and reusability. A reusable format only works if the system is adjusted to account for it. Sustainable design and other concepts come into play here. For example, reusable systems for carry-out food service are expanding in cities. Learning from these systems and understanding trade-offs will help expand reusable options for consumers.

MARCUS: I think we also need to recognize that when we’re talking about systems, we’re also talking about our current political and social context. Municipalities have finite budgets for waste management. The pandemic has created an economic strain and tremendous challenges which have slowed the discussion on innovative waste management. This provokes the conversation of who is going to pay for managing the flow of materials in a circular economy. In addition, the pandemic has pushed us into a recession, which will likely continue to impact municipal budgets in the longer term. The pandemic shows us that gaps in waste management infrastructure are not limited to the developing world. Moving to a more resource-efficient circular economy is a way to reach these goals, and drives the conversation upstream to the design of products, materials used, and systems in place to get those materials back.

Reuse models and residual management

MERIDIAN: You both brought up reuse, which seems to be key to developing a circular economy. How can we embrace reuse models and transition waste management systems towards that end?

MARCUS: We need to develop approaches that encourage a reuse economy and eliminate low-value, high-polluting residual materials that are difficult to reuse. When it comes to packaging food, reuse necessitates consideration of issues such as shelf-life, food safety, and disposal after consumers are finished with a product. This means we need to rethink systems for distributing materials in waste-free packaging, incentivized methods of collection, washing and repacking of durable containers, etc. There are many innovative entrepreneurs testing these business models.

STEW: Yes, and if companies can figure out how to implement the complex logistics necessary to guarantee two-day shipping, it should be possible to figure out how to transport recyclables and other collected materials to where they can be handled properly. The collective brainpower of stakeholders in the plastics community is needed to address some of these challenges. There is an immediate need to manage residuals that cannot be recycled or entered into secondary markets, in an environmentally-sound manner. The role of waste collectors and the informal sector can be amplified to safely collect and sort materials.

Business is good at getting products to the most remote places on the planet, but the return voyage is left to cities and taxpayers. This is the essence of the challenge with the linear economy. (Marcus)

MARCUS: Many of the environmental NGOs that I work with, including social justice and zero-waste organizations, can already point us to successful models of zero-waste cities. In the Philippines, for example, composting organics on site and improving sorting has led to positive externalities such as economic gain and a reduced need for garbage trucks to move goods. A circular economy is possible when materials have high enough value to incentivize their collection; there is then a corresponding business case for scaling the successful zero-waste cities models.

However, we still need innovative business models that can replace the most common low-value residuals with a waste-free alternative to meet the need that product fulfilled. For example, sachet packets wrapped with a thin coating of polyethylene could be replaced with a bio-based material or a product delivery system that relies on bulk item kiosks that let you fill your own containers. These business models exist and are showing the world a viable alternative. We are seeing municipalities and NGOs asking industry to invest in or subsidize these efforts so they can capture enough market share to compete.

STEW: I can only speak on behalf of my organization and our perspective that resin producers do have a role to play in supporting solutions, but there are also a variety of opinions when it comes to subsidies versus incentivizing markets and other solutions. Still, significant change will require collective commitment, a mix of solutions, and adaptations, including transitioning from our current system of disposable goods and packaging to a future system that relies on reusable goods and minimal or reusable packaging. This calls for innovators to redesign existing systems, including infrastructure changes to food and water delivery systems from a disposable to recyclable or reusable formats. We also need to find, embrace, and strive for zero-waste concepts. As we improve sorting (beginning with improved local collection and processing of organics), we increase the value of materials and create the secondary post-consumer market.

ACC represents the resin producers, but this is a discussion that requires a much broader community comprised of other stakeholders in the value chain: brands, retailers, recyclers, plastics converters, community stakeholders, environmental stakeholders, government officials, and more. Opportunity lies in coming together to identify the policy, infrastructure, and innovations that can transition our current reality into the future we want.

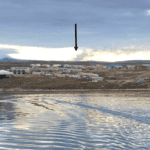

PLASTIC POLLUTION IN POLAR REGIONS

The high Arctic is perhaps the last place you’d think of when you picture plastic pollution, but it is in fact the perfect illustration of the problem with a linear economy. Despite community initiatives to reuse and recycle materials, waste abounds in a region without clear avenues for materials management. Marcus’s recent paper on plastic in polar regions details the problem: Pond Inlet, a village of only 1,200 residents in the Canadian Arctic, is left with piles of waste including both durable goods (e.g., furniture, e-waste, car parts) and an abundance of single-use plastics. What to do with all this junk? Without the funds to transport materials, they set their landfill on fire. Unfortunately, this practice is common globally, and this example supports our need for a circular economy, including allocation of funds for improved materials management.

What about banning plastics?

MERIDIAN: What about policies that ban the use of certain plastics (generally single-use items) like plastic bags?

MARCUS: The idea of bans itself comes from a larger zero-waste cities framework, which has shown success. Worldwide, environmental organizations, restaurants, businesses, and governments in the EU, Canada, recently Kenya, and many other localities are looking at eliminating single use plastics because they are the lowest value materials with the highest leakage into the environment and accumulation in communities. The current system allows the market to drive the change, which relies on demand of materials. Since the single-use plastic materials are cheaper, there is no incentive in a market-based system for buying higher quality materials and goods, or to recycle plastic when virgin resin is cheaper.

If you take into account the true cost of single-use plastics—which means including ecological and economic impacts—the costs outweigh the benefits. The environmental community favors bans because they level the playing field, allowing innovators to provide novel, less harmful solutions.

STEW: We approach bans differently, but zooming out, this illustrates why I think these conversations are useful in helping to broaden my perspective, the perspectives of industry, and the perspectives of environmental NGOs. It’s so important to look at these issues through multiple lenses and not just through our own perspective. Marcus, your perspective has shown me that there’s an opportunity to create incentives and encourage alternatives. We should encourage better sorting closer to the point of product use, like in the Philippines example. That way, the product is cleaner and of higher value to the secondary market. The business community prefers this approach, but it’s important that we recognize each other’s perspectives and roles, and the trade-offs to both approaches.

Barriers and trade-offs

MERIDIAN: Let’s talk more about those trade-offs…

STEW: It is important to balance the economic, social, and environmental trade-offs in bridging our present reality with the future we want. We should work together to identify trade-offs and determine which ones to prioritize based on their importance. Working with government officials and policymakers next, we can build balanced solutions.

We can’t forget that plastics do provide significant benefits to society, including the reduction in GHG emissions compared to alternatives, decreased fuel usage, and increased efficiency in transport due to the lightweight nature of the material. However, when used plastics are not properly managed, they end up in the environment, jeopardizing the benefits. Therefore, it’s critical to manage trade-offs within a specific policy context.

MARCUS: For many NGOs, the conversation is largely about how to capture the negative externalities of plastics. If we’re going to calculate the positive externalities, you’ve got to factor in the negatives too. It’s a “True Cost” analysis that we often use to defend the decision to ban a single-use plastic item. Depending on the type of plastic (e.g., durable goods, single-use packaging) and its use, the true costs differ. I’ve sailed around the world and walked some of the most remote coastlines. I have not seen a single car bumper or computer floating in the ocean or washed ashore, but I have seen countless plastic bottles, caps, straws, and bags. This illustrates how the negative externalities and true costs of different products vary and require different conversations about waste management.

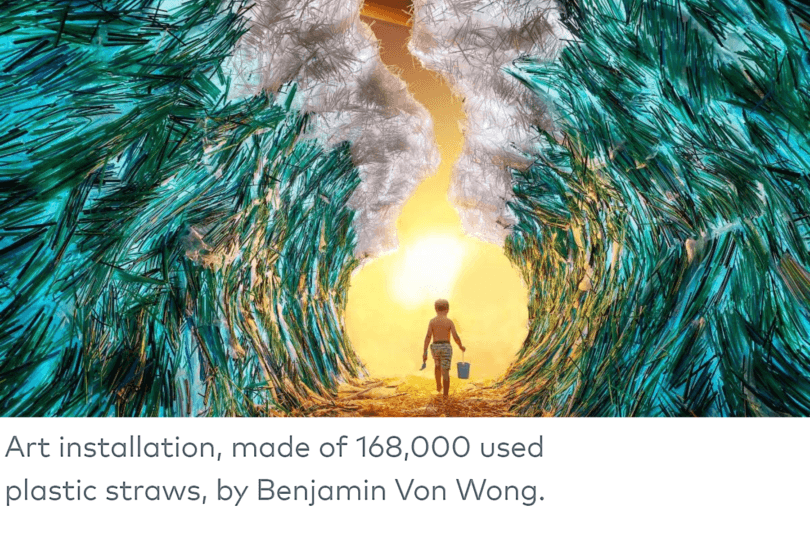

We should focus on ways to mitigate and minimize the harm caused by single use packaging. Year after year, data from global coastal cleanups identify the most frequent plastic waste culprits. They are a small group of single use plastic products: items like packets of shampoo, cigarette butts, food wrappers, straws, and beverage containers. It turns out that these same items are found on land and in the sea. Taxpayers and cities do pay to try to manage the harm they cause, but frequently, adequate waste management systems don’t exist. Unfortunately, the default in many parts of the world is open pit burning.

COASTAL CLEANUP DATA

Data from the Ocean Conservancy shows the Top 10 most commonly collected items globally during the 2019 International Coastal Cleanup were:

1. cigarette butts; 2. food wrappers (candy, chips, etc.); 3. straws, stirrers; 4. forks, knives, spoons; 5. plastic beverage bottles; 6. plastic bottle caps; 7. plastic grocery bags; 8. other plastic bags; 9. plastic lids; 10. plastic cups, plates

Can we get rid of these items? Can we find innovators to help industry make a fortune producing different kinds of reusable containers? There’s a huge market for innovation, so let’s get rid of the products which have many trade-offs on the back end. To make this clearer, consider that effective models already exist, such as the Zero Waste Cities models in New Zealand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. We can move forward, acting on some of the proven systems that we already have.

Looking to the future

MERIDIAN: From talking with you, it is clear you both agree that society is unable to manage the quantity of plastics we produce today. Yet, if current projections for plastic production over the next decade are accurate, the quantity of plastic produced in the coming years will far exceed what we produce now. How can we use the common values and viewpoints that have emerged in this conversation to move forward in building solutions? How can we bring other industry and NGOs leaders closer together to solve this massive problem?

MARCUS: That’s a challenging question. Looking ahead, industry and environmental NGOs each make their projections based on the future they want. Industry projections for increased production are based on population growth, a rising middle class, and demand for the material. In one estimate I’ve seen, the world may produce 1 to 1.2 billion tons of plastic per year by 2050. Of course, environmental NGOs are pushing for the exact opposite trend: a significant reduction of plastics, especially single use plastics. Continuing our dialogue with larger groups of stakeholders (resin producers, CPG companies, NGOs, scientists, startups, etc.) could help bridge this disconnect.

Opportunity lies in coming together to identify the policy, infrastructure, and innovations that can transition our current reality into the future we want. (Stew)

STEW: It’s very telling that we agree on the need to bring together a larger group of stakeholders to envision the future that we want. And, that it’s not just about more or less plastic production—it’s about building future systems that deliver the benefits that plastics provide, reducing leakage to the environment, increasing access to environmentally sound management of waste, increasing reusables, developing new delivery systems, and more. These are all future opportunities that we want to see.

The projections for plastic production are based on the assumption that the rising middle class will consume more goods. The question is: how do we envision a future where the rising middle class has access to a higher standard of living but doesn’t necessarily produce the waste that we see today?

Envisioning the type of future we want—at a bigger picture level—is the focus of this discussion. As we identify that future, what are the actions we need to take? What are the investments we need to make? What are the policies that need to be changed so that we can achieve a reduction of leakage to the environment over time? It’s not going to be an overnight transition. Bringing together a larger group of stakeholders—scientists, industry representatives from across the value chain, together with environmental groups—will help us identify the future we want. Right now, as a society and as individuals, we are reflecting on our past and planning the future we want to see on multiple fronts. This conversation is simply a milestone on our long journey.

Call to action

MERIDIAN: Thanks to you both for your willingness to engage in this dialogue and for your candor and your enthusiasm. This conversation has illustrated many shared values and objectives, especially around reducing harm and reducing leakage in the environment and finding solutions that are economically viable. It is constructive to consider the problem from different perspectives to ensure that we are addressing system as a whole. How can we invite others to join this type of dialogue in the future?

STEW: We need to provide entry points for alternative solutions, since the two of us can’t solve this problem alone. Our conversation has identified an interesting opportunity for collaboration. If we can get other thought leaders within our various communities across the plastics value chain and environmental groups to come together to recognize a shared end goal, it will be more possible to achieve it.

First, there are competing interests and environmental, social, and economic trade-offs that need to be understood and considered. Although business models are created in certain ways, companies and businesses need to evolve over time in order to survive and sustain themselves. This is the perfect area for a larger group discussion. Let’s figure out how we can create opportunities for the innovators and how we can adjust the system to allow for change, understanding that market forces might not be or are not yet sufficient. We need key players from multiple perspectives to be willing to give it a go. Let’s roll up our sleeves.

MARCUS: I agree. It’s essential to continue bringing multiple stakeholders together, so that we’re not spending time and resources talking at each other when we could move in the same direction. Meridian and others have been doing this over the last couple of years and more of that is needed, including a deep dive into some real-world examples, like the zero-waste cities model. Around the world, there are many pilot programs testing solutions to the plastic waste problem. We must approach this problem as honest brokers envisioning the future we want for the next generation. I really look forward to more opportunities to explore this with you, and I want to thank everyone for keeping this conversation going.

Note to the Reader

A Path Forward

If you are interested in pursuing or supporting multiparty solution building on plastic waste, please reach out to Meghan Massaua to share your ideas. We are eager to put our skills to work to expand conversations like these to pave the way for implementation of broadly supported collaborative solutions. We see a clear opportunity to continue to build relationships and leverage significant momentum to showcase solutions, highlight new initiatives that can address pressing challenges facing our environment, and inspire partnerships. We are working to build trusted spaces to welcome diverse viewpoints to address these very important issues.